The Summit asked: How do rural communities sustain journalism that supports democracy?

|

| Penny Abernathy of Northwestern University was the first presenter at the rural journalism summit. |

|

| Tom Silvestri |

The challenges of rural journalism are mainly the challenges of the communities it tries to serve, and many of those challenges are daunting. But they are not dispositive. That was made clear at the National Summit on Journalism in Rural America by some sharp, innovative and courageous editors, publishers, academics and other journalism supporters.

"Community newspapers are still trusted" more than other news media, said Lynne Lance, executive director of the National Newspaper Association, citing at Friday's opening session the recent survey done for NNA in its the markets of its members, mainly weeklies and small dailies.

But more broadly, when you ask how America's rural newspapers are doing, you also need to ask, and answer, this question: "How is rural America doing?" said longtime Georgia publisher Robert M. Williams Jr.. "It's hard for any newspaper to ever rise above the quality of the community it operates in," but there are exceptions, he said Friday.

|

| Tony Baranowski |

For many older newspaper owners in small towns, the biggest problem is finding an acceptable buyer for their newspaper.

"What we see are thousands of independent owners across the country who want to leave their legacy but don't have someone to buy their paper," Elizabeth Hansen Shapiro of Columbia University said Saturday morning. She is founder of the National Trust for Local News, which tries to keep local news media in local hands, rather than profit-motivated chains or politically motivated buyers.

"It's obvious by the quality of what they're doing that they're not in it because they love newspapering," said Sharon Burton, editor-publisher of the Adair County Community Voice in Columbia, Ky.Some owners who don't want to sell to such buyers just close their papers, and some such buyers eventually merge or close them, or strip them down so much they create what Penny Abernathy of Northwestern University calls a news desert: a community "with limited access to the sort of credible news and information that feeds democracy at the grassroots level and helps residents make wise decisions about issues that will affect their quality of life and that of future generations."

In some cases, that means a "ghost newspaper." In others, it means no paper at all. Abernathy, who has tracked the trend for years, said Friday that the recent rate of mergers and closures is double what she expected, and they are now being seen in affluent communities. She is in the midst of writing an update of her research.

Oregon has lost a fourth of its newspapers since 2004, said Jody Lawrence-Turner, executive director of the Fund for Oregon Rural Journalism. She said half the incorporated cities in the state lack a local news source: "Nobody is watching them."

|

| Bill Horner III |

Horner said his twice-weekly lost its largest single-copy vendor (three stores, 200 papers) because his sports editor told the owner that the paper was doing a story on the history of lynching in Chatham County. But he said he continues outreach to Blacks and Hispanics, each 12 to 13 percent of the county's population, because sustainability relies on engagement and helping audiences solve their problems. He said one recent success is a parenting newsletter, because most people are parents, and that crosses the social and political divides.

Baranowski said, "We have to embrace immigration, refugees, wherever they're coming from." His PowerPoint presentation said, "These are facts that are difficult for many of our overwhelmingly white communities to embrace, but we have to illustrate the successes" of embracing immigrants and refugees. He said "The community is not embracing their stories," one exception being an Afghan who was an interpreter for the American military. "Never underestimate the value of people being proud of lifting up an underdog," he said.

Dink NeSmith, a newspaper chain co-owner who came out of retirement to save The Oglethorpe Echo in northeast Georgia and made it a nonprofit staffed by University of Georgia students, said Saturday, "We began to cover the Black community for the first time," The county is 17% Black. He said a Black truck driver was appreciative, and donated $500.

"We see nonprofit local news . . . as a real bright spot," said Jason Alcorn, vice president of learning and impact at the American Journalism Project, which makes grants to nonprofit news organizations, partners with communities to launch new ones, and coaches their leaders.

Publishers who are interested in the nonprofit model can explore it with the help of the Institute for Nonprofit News, which has more than 400 nonprofit, nonpartisan publishers doing 400,000 stories a year, said Jonathan Kealing, the organization's chief network officer.

INN publishes a conversion guide, developed with the Salt Lake Tribune, which recently went nonprofit, and a guide for nonprofit startups. It also provides advice for its members.

Alcorn and Kealing appeared with Elizabeth Hansen Shapiro of Columbia University, co-founder of the National Trust for Local News, which aims to keep local news in local hands. Last year, it used philanthropic support to buy a chain of 24 community newspapers and put them in a nonprofit. Now, she says the Trust is asking, "How can we bring rural papers together under common nonprofit ownership to share resources and increase the chances of long-term service and sustainability?"

A fundamental difference between the profit and nonprofit models is that the former is about making money and the latter is about providing public service. "Nonprofits are by law community assets" that can't be sold, and their boards are charged with acting for the benefit of the community, not the benefit of the organization, Kealing said.

A nonprofit can still make money; it just re-invests profits rather than distributing them to owners. "Nonprofit does not mean non-commercial," Alcorn noted.

|

| Liz Parker |

"The options for selling we so unattractive," Steve Parker said. His sister said most of the buyers were "bottom feeders" who would have ruined the papers, so they created the Corporation for New Jersey Local Media, using the model of the Lenfest Institute, which owns the Philadelphia Inquirer: a social benefit corporation ("B corp") that allows the papers to keep publishing editorials and anything else a paper can do, including events. The CNJLM can also take grants and tax-deductible contributions.

It can also acquire other papers, becoming an umbrella for independently operated news organizations. Amanda Richardson, executive director of the nonprofit, said it has been approached by another paper that may become part of the enterprise.

Liz Parker said the model is sort of like the people of Green Bay, Wis., owning the Packers, but there is no reason that it can't work "across the country." Her detailed PowerPoint presentation can be read and downloaded here. Shapiro's presentation is here.

Some university professors and journalism programs are helping rural newspapers; one prof says it's about time

As more higher-education journalism programs try to serve community journalism, one professor who started a newspaper with her students, is doing hands-on research and testing a new business model at two weekly papers says the efforts are long overdue.

|

| Teri Finneman |

"Where the hell has the ivory tower been the last 20 years?" Finneman asked. "We are the ones who should have been leading the research, working with the industry, to avoid this mess that we are in right now. . . . It is time for the ivory tower to step up and support our counterparts in the industry."

Finneman is a researcher of journalism history, but she has launched into doing journalism with her students, as publisher of the Eudora Times in a small town nine miles from her journalism school, which will host "News Desert U." Oct 21-22 for journalism educators to address the crisis. "It is time for universities to step up, finally, and do something about this," she said.

This summer, Finneman is testing a new business model for community papers at Harvey County Now in Newton, Kan., and the Hillsboro Free Press, which will get $10,000 to participate. The model aims to get more revenue from the audience with e-newsletters, events and two tiers of memberships. Kansas Publishing Ventures, which owns the papers, is keeping detailed minutes of its weekly meetings on the project, to help develop an information packet for community papers across the nation, Finneman said.

The model is based on surveys that Finneman and other researches did in Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas, which found that newspaper readers are much more willing to support their papers with money beyond subscriptions that newspaper publishers think they are. In North Dakota, the only state where she has released her results, 40 percent said they were likely or very likely to donate.

Finneman said she and her colleagues were "taken aback" at the attitude of publishers in focus groups who felt that asking for voluntary support would be admitting failure or showing personal weakness. "They very much saw themselves as a business, as opposed to an unreplaceable civic community organization that a newspaper is," while "leaving free money on the table."

She said publishers cited the lack of time and resources for business-model experimentation, but "Overall, there was very much this underlying fear, the fear of doing something different."

|

| M. Clay Carey |

The summit's "research question" was "How can rural communities sustain local journalism that supports local democracy?" Carey said we need research that is centered on the idea of democratic practice, and the essential role of agency: the ability to act on information. He said research has focused on information at the expense of focus on agency, which many people feel they don't have, and suggested more specific research questions" How can journalistic organizations equip people to be civically engaged? How can they encourage and empower them? Perhaps by "inviting people to participate in sharing their story," he said.

More broadly, he said universities should ask, "How can news organizations facilitate collaboration that creates a sense of community and creates positive change?" and think about facilitating collaboration among local newspapers, national and regional organizations, and local entities such as libraries. He said universities can help create frameworks, and reduce risk and risk aversion. And all the while, do research that is "accessible to people outside the academy. . . . It's easy for research to be an extractive industry, in the same way that journalism can be an extractive industry."

|

| Bill Reader |

Beyond research, some university journalism programs are trying to help individual papers and the industry at large. University of Georgia students staff The Oglethorpe Echo, a nearby paper that was going to close until retired chain publisher Dink NeSmith created a nonprofit and got the university involved (he described the process in the first Saturday afternoon session); and West Virginia University has the NewStart program to train the next generation of community newspaper owners. Its director, Jim Iovino, reported that the University of Texas is sending someone to see how it can emulate the effort. In both states, newspaper associations asked universities for help because newspaper owners could not find acceptable buyers for their papers.

How philanthropy can help rural news media, individually and collectively

|

| Nathan Payne |

|

| Dennis Brack |

Brack said the paper and Foothills Forum are independently operated, with an operating agreement that is public, along with the names of donors, but are "highly collaborative." The only direct subsidies have been sharing the match for RFA reporter and picking up the pay for a part-timer during the pandemic.

|

| Jody Lawrence-Turner |

FORJ's first big pilot project addresses a growing complaint of rural editors and publishers: They can't find qualified people who want to work in local news. One solution often suggested is developing interest and talent among students in high school or even middle school. FORJ's Future Journalists of America pilot at four high schools in Bend newsrooms hosts a lab with sessions taught by professionals in a semester-long curriculum: media literacy, professional craft, doing assignments with news staffers, a digital, district-wide publication, and exploration of sustainable business models. The overall goal is to sell "a career with a purpose, ensuring the continuation of a free democracy," Lawrence-Turner said.

The Summit session on "Putting Philanthropy in Your Business Model" is on YouTube, here.

Philanthropy was mentioned in other sessions. Elizabeth Hansen Shapiro of the National Trust for Local News discussed how the Trust and philanthropic partners bought a chain of 24 community papers in Colorado and put them into a nonprofit, creating an umbrella model for other places.

The Trust, the Institute for Nonprofit News, the Kentucky Press Association and the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues (sponsor of the Summit) have conducted a survey of newspaper owners in Appalachian Kentucky with the Mountain Association, an Appalachian Kentucky development organization that wants to keep the papers in local hands, perhaps using a nonprofit umbrella for those in distressed counties where for-profit buyers either wouldn't be interested or could damage the papers.

Philanthropy would be needed to fund such a model, but that challenge could also be an opportunity. If an umbrella nonprofit was also committed to improving coverage of regional issues, across the county lines that typically define rural newspaper markets, that could attract funders. "Successful papers don't think geographically" but are "breaking out of geographic jail," Penny Abernathy of Northwestern University said at the Summit's opening session, which is here on YouTube, along with other sessions.

The revenue-raising stories of two rural community newspapers

|

| Terry Williams |

|

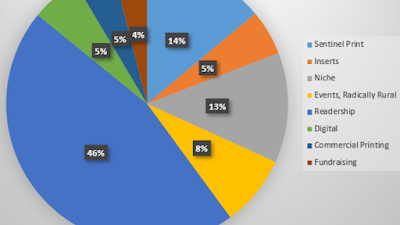

| CHATHAM NEWS-RECORD REVENUE CHART |

In a written Q and A with Ryan, Horner said his paper will "have to focus on new revenue streams and be reader-driven." It is raising prices and getting "blowback from some readers and even dealers, but it’s a value proposition: sometimes you support the value of your work with higher pricing."

Asked what partnership has been the most lucrative or profitable, Horner said the News+Record's promotion of nonprofits helped prompt the local Council on Aging, "which is really a county department but mostly funded privately," to use two pandemic-relief grants "to give us $10,000 to provide subscriptions to senior citizens they serve who didn’t subscribe. We also got $18,000 in financial support from Mountaire Farms, a poultry processing company with Spanish-speaking employees, for our La Voz project to bring a Spanish-language publication, La Voz de Chatham (Voice of Chatham), to the community."

Williams noted the Sentinel's partnership with the local Hannah Grimes Center for Entrepreneurship on Radically Rural, a multi-track community development symposium that includes a track on community journalism. The other tracks are entrepreneurship, downtowns, land and community, arts and culture, clean energy and health care. "It has been profitable for both partners and a boost to the local community," Williams wrote We have won numerous regional and national awards for Radically Rural, including third place for Virtual Events from the Local Media Association in 2020. Feel free to join us Sept. 21 and 22, 2022, either virtually or in person."

Ryan's final question: "Now that you’ve gotten to know each other, what’s the best idea you plan to steal from your new friend?" Horner said of Williams, "I particularly like the direct personal appeals he and his staff do by email to readers and contacts; we have already built a plan to replicate that. And I loved his Community Impact Report. What a great way to tell your own story and demonstrate your value to your audience." Williams said, "Bill’s team produces a handsome, helpful community resource guide (Chatham 411) that is heavily supported by advertising. We are looking at producing something similar for our market, and Chatham News+Record’s product is an excellent model for us. It’s very well done."

Good journalism is good business, rural editor-publishers testify

The research question posed by the Summit was "How do rural communities sustain local journalism that supports local democracy?" We phrased the question that way to make the point that the sustainability of rural journalism depends more than ever on the communities it serves. In other words, it will need to get more of its revenue from its audiences, and that will require engaging more with those audiences and giving them real value for their money. As I said at the Summit, "People aren't going to pay good money for bad journalism."

Doing good journalism in rural areas has always been more difficult than in urban areas, because there are fewer resources and often less willingness to run against the grain. The latter factor has become more common lately, as the divisiveness of national politics changes the character of local politics in some places. But there are ways to turn both challenges into opportunities, and we explored that in several Summit sessions, including one called "Good journalism is good business."

The speakers for that session were two editor-publishers of excellent weekly newspapers that are not the only papers in their communities, but are financially successful: Sharon Burton of the Adair County Community Voice in Columbia, Ky., and Marshall Helmberger of the Timberjay in Tower, Minn. In the hills of Southern Kentucky to the forests of Northern Minnesota, both try to be relevant.

|

| Marshall Helmberger |

"They know when it comes to our investigations we don't play favorites," Helmberger said. "Over time, the light bulb clicks on and they realize newspapers can play an important role in bringing positive change to the community. . . . We don't just have readers. We have engaged readers who can't wait for the next issue." That showed when the Timberjay was the target of a frivolous lawsuit that would still take a big part of its annual cash flow to defend. Crowdfunding for the defense raised $30,000, Helmberger said, and one reader paid for a $35 obituary with a $500 check and said to keep the change.

Both Helmberger and Burton have played unusual – and probably for most journalists, controversial – roles in their communities. Helmberger is the executive of the local economic-development authority, and Burton served on the board of the local hospital that had been driven into bankruptcy by mismanagement. When the new county judge-executive asked her to serve, she had many reservations because journalists are supposed to cover news, not make it. But she agreed "because I could not think of anything more important to do as someone who loves this community and the people who made it great," she wrote, adding that she felt she could make sure the board was more transparent than it had been. She recused herself from reporting or editing any hospital stories, and had an outside professional edit them for publication. For more on Burton's exploits, click here.

Burton told the Summit crowd that when she told the judge-executive (the county's elected administrator) that she liked her but that wouldn't affect her watchdog reporting and commentary, the official replied, said "That's why I try to make sure I don't do anything wrong." Burton said, "I don't think that you can get a greater compliment in your town . . . that they'll acknowledge when they make decisions, they think about you. You know? And that's what we should be in our communities. That's what we're supposed to be."

|

| Sharon Burton |

Burton concluded with a personal statement that many independent editor-publishers would make, and one that could be useful in reassuring or alerting readers concerned about owners' motives: "I make money so I can be in the newspaper business. I'm not in the newspaper business to make money," as she said most buyers of newspapers are today. "It's obvious by the quality of what they're doing that they're not in it because they love newspapering. I think they're part of our problem, because they hurt our reputation."

Speakers in other sessions gave other ideas for rural journalism that serves the public and helps make money. Penny Abernathy of Northwestern University, who popularized the term "news deserts," said that as the deserts appear, irrigation can come from across the county line: "Successful papers don't think geographically" but are "breaking out of geographic jail" with news coverage and advertising sales, she said.

Abernathy also passed on a line about the value of community journalism that could be a good pitch for subscriptions: "It helps you realize whom you're related to that you didn't know."

|

| Jim Iovino |

Iovino also touted electronic newsletters on particular topics, which "can turn weeklies into seven-day brands by creating a daily check-in for readers" and competing with social media. He noted the advice of the Table Stakes program: "Audience first, digital first, print better."

Tom Silvestri of The Relevance Project of the Newspaper Association Managers promoted his central idea of the local newspaper serving as "THE Community Forum."

In today's media landscape, Silvestri said, "I wouldn't launch a newspaper or a website, I'd launch a forum. He said that as publisher of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, he did 78 "public squares," and offered a set of tools for replicating that work, down to the layout of the seating. He said forums on local issues don't cost much to do, but can build audience, and "You can make money off an audience." Also, the experience can help you do paid and sponsored events that generate income.

|

| Dink NeSmith |

"I cannot praise the students enough," NeSmith said, citing a Black truck driver who made a big donation to the nonprofit and a reader who said, "There's actually something to read in that damn paper now."

NeSmith said the weekly is also engaging readers by asking them to write essays answer the question, "Why do I love Oglethorpe County?" That's uplifting, engaging and inviting, and that's what we need.

No comments:

Post a Comment