|

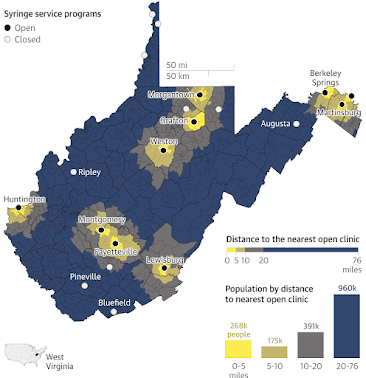

| Most residents of West Virginia now live more than 75 miles from a sterile-syringe program. (Graphic by The Guardian; click on it to enlarge) |

"The new law requires programs to offer a range of health services in addition to the exchange, only serve people with a West Virginia ID card, and aim to get one used syringe back for each new one they give out," Quenton King reports for Mountain State Spotlight.

However, it's difficult to assess the impact of HIV in rural areas: To preserve patients' privacy, the state's health department only releases ballpark numbers, King reports. That means even county health departments are in the dark about the local extent of the problem, and they are generally left out of the loop on HIV cases.

Robin Pollini, a substance-abuse and infectious-disease epidemiologist at West Virginia University, "says that it should be considered a significant concern when HIV appears in any county that previously had no cases, but especially in rural counties where access to care is limited," King reports. "There are actions that counties can take — from ramping up testing to creating harm reduction programs — by just knowing the number of HIV cases popping up in the county."

But local agencies might have a difficult time responding even if they knew about new cases. "With the current landscape — stressed by Covid, underfunded, and with new laws restricting the types of harm reduction programs they can offer — county health departments have few opportunities to address potential outbreaks, even if they see them coming," King.

No comments:

Post a Comment