Growing up, I often heard from my parents that I needed to “get out of here.” And I did get out, from Ohio’s Appalachian foothills to a university near Cincinnati. Not far in terms of miles, but light-years in lifestyle. My trajectory from a trailer park in a small town to a two-story house in a subdivision was tenuous, but ultimately successful. For many students in Appalachia, though, college is an impossible dream.

The rate of bachelor’s degree attainment or higher in rural, Appalachian Ohio is 18.6 percent, compared to 31 percent for non-Appalachian Ohio. This trend reflects the national dynamic between rural students and college-going.

Yet this is in an era when demand for college graduates is soaring. While many factors play into this relative lack of rural postsecondary education, there are concrete, common-sense policies that school districts can put in place to change it, including increasing high school rigor and providing more Advance Placement and dual-enrollment courses.

My own journey was difficult. I wasn’t prepared. Even though I scored well on the ACT exam and took the most advanced courses my high school offered, in my first semester of college I was placed on academic probation. In addition to the academic challenges, managing the financial burdens of living independently left me with limited time to catch up.

I did make it through to graduation, though, and went on to graduate school. The reason? Luck. I got a union job that offered consistent hours and benefits. I found a landlord who gave me a discount on rent and had a family member near the college that supported me financially and emotionally. Remove any one of those girders and I would have ended up in a much different place.

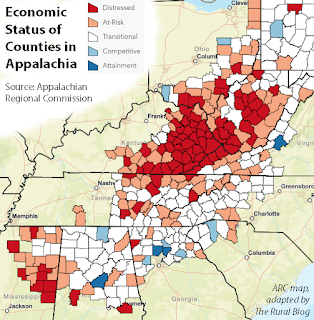

In other areas of Ohio, having the academic readiness and supports to persist in college is not based on luck. It’s systemic. My home county is one of five in Appalachian Ohio designated as “economically distressed,” meaning that we have significantly higher rates of poverty and unemployment and a lower median family income relative to U.S. averages.

Among the 22 school districts within these five counties, less than half had any level of student participation in AP courses. Of those, most had AP participation rates near or below 10 percent of the student body. This matters because AP course participation and completion with a score of 3 or higher on an AP exam is positively correlated with college persistence. Similarly, many of these districts also have a low percentage of the student body that is ready for college as measured by the ACT’s “remediation free” cut score.

These facts mean that college readiness remains an enormous challenge for Appalachian Ohio, an observation supported by research. In my own experience, also echoed by research, completion of college is associated with many social and economic benefits. Moreover, there are immediate societal impacts.

Opportunity Nation, a campaign by Child Trends and the Forum for Youth Investment, created the Opportunity Index, a measure of economic and educational opportunities for communities across America. A key metric in the index is the percentage of disconnected youth — neither working nor enrolled in school or college — between the ages of 16 and 24.

Let’s be clear, not everyone needs to go to college. But we must not kid ourselves that “pathways” policies are somehow offering “choice” or “flexibility.” They are reducing many students’ choices by ensuring that they are not prepared to succeed in college should they later choose to attend.

School districts can take steps to improve college readiness, such as providing a more rigorous high school curriculum that emphasizes AP courses. It’s not a cure-all, but other Appalachian areas have shown positive results with such policies — especially when paired with professional development for teachers that helps them add that academic rigor and trains them to teach AP courses. Fortunately, such professional development courses already exist and need not be created from scratch. What is needed is a district-level emphasis to make such training and courses a priority. And the funding is there: Appalachian Ohio has access to grants through the Appalachian Regional Commission as part of the workforce ecosystems investment priority.

Some people assume that the reason for lower college education rates in Appalachian Ohio is simply that there is less need for a college degree there. Mining and farming are the most common industries associated with the area. But while these industries are more prevalent in Appalachia than in the rest of the U.S., they make up a small fraction of the region’s total industry. Further, the proportion of service industry jobs in Appalachia, including professional and technical services, is nearly equal to that in the rest of the U.S. — just over one third of all jobs.

This is not a problem of economics; it’s a problem of expectations.

My college education was a ticket out of poverty, one that too many students in Appalachian Ohio find impossible to obtain. I often wonder where I would have ended up without it. Among the 20 percent not working and not in college? Or among the hundreds who’ve died of overdoses in the region?

I can put names to those statistics. I’ve seen the consequences of a lack of opportunity. We must do better.

David L. Adams is a school psychologist and Ph.D. student at the University of Cincinnati, where he researches impacts of education policy on Appalachia. This was published by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent newsroom focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Yet this is in an era when demand for college graduates is soaring. While many factors play into this relative lack of rural postsecondary education, there are concrete, common-sense policies that school districts can put in place to change it, including increasing high school rigor and providing more Advance Placement and dual-enrollment courses.

My own journey was difficult. I wasn’t prepared. Even though I scored well on the ACT exam and took the most advanced courses my high school offered, in my first semester of college I was placed on academic probation. In addition to the academic challenges, managing the financial burdens of living independently left me with limited time to catch up.

I did make it through to graduation, though, and went on to graduate school. The reason? Luck. I got a union job that offered consistent hours and benefits. I found a landlord who gave me a discount on rent and had a family member near the college that supported me financially and emotionally. Remove any one of those girders and I would have ended up in a much different place.

In other areas of Ohio, having the academic readiness and supports to persist in college is not based on luck. It’s systemic. My home county is one of five in Appalachian Ohio designated as “economically distressed,” meaning that we have significantly higher rates of poverty and unemployment and a lower median family income relative to U.S. averages.

Among the 22 school districts within these five counties, less than half had any level of student participation in AP courses. Of those, most had AP participation rates near or below 10 percent of the student body. This matters because AP course participation and completion with a score of 3 or higher on an AP exam is positively correlated with college persistence. Similarly, many of these districts also have a low percentage of the student body that is ready for college as measured by the ACT’s “remediation free” cut score.

These facts mean that college readiness remains an enormous challenge for Appalachian Ohio, an observation supported by research. In my own experience, also echoed by research, completion of college is associated with many social and economic benefits. Moreover, there are immediate societal impacts.

Opportunity Nation, a campaign by Child Trends and the Forum for Youth Investment, created the Opportunity Index, a measure of economic and educational opportunities for communities across America. A key metric in the index is the percentage of disconnected youth — neither working nor enrolled in school or college — between the ages of 16 and 24.

Let’s be clear, not everyone needs to go to college. But we must not kid ourselves that “pathways” policies are somehow offering “choice” or “flexibility.” They are reducing many students’ choices by ensuring that they are not prepared to succeed in college should they later choose to attend.

School districts can take steps to improve college readiness, such as providing a more rigorous high school curriculum that emphasizes AP courses. It’s not a cure-all, but other Appalachian areas have shown positive results with such policies — especially when paired with professional development for teachers that helps them add that academic rigor and trains them to teach AP courses. Fortunately, such professional development courses already exist and need not be created from scratch. What is needed is a district-level emphasis to make such training and courses a priority. And the funding is there: Appalachian Ohio has access to grants through the Appalachian Regional Commission as part of the workforce ecosystems investment priority.

Some people assume that the reason for lower college education rates in Appalachian Ohio is simply that there is less need for a college degree there. Mining and farming are the most common industries associated with the area. But while these industries are more prevalent in Appalachia than in the rest of the U.S., they make up a small fraction of the region’s total industry. Further, the proportion of service industry jobs in Appalachia, including professional and technical services, is nearly equal to that in the rest of the U.S. — just over one third of all jobs.

This is not a problem of economics; it’s a problem of expectations.

My college education was a ticket out of poverty, one that too many students in Appalachian Ohio find impossible to obtain. I often wonder where I would have ended up without it. Among the 20 percent not working and not in college? Or among the hundreds who’ve died of overdoses in the region?

I can put names to those statistics. I’ve seen the consequences of a lack of opportunity. We must do better.

David L. Adams is a school psychologist and Ph.D. student at the University of Cincinnati, where he researches impacts of education policy on Appalachia. This was published by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent newsroom focused on inequality and innovation in education.

No comments:

Post a Comment