By Al Cross

Director and Professor, Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, University of Kentucky

The owner of dozens of "ghost newspapers" bought from Gannett Co. says he is trying to revive them by returning editorial decision-making to local people while still taking advantage of the economies of scale that have led to consolidation of newspaper ownership. But he says his new chain's fate is not in its own hands.

"The success or failure of these rural newspapers is on the local people," CherryRoad Media CEO Jeremy Gulban said Friday at the National Summit on Journalism in Rural America, sponsored by the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, publisher of The Rural Blog. His remark fit the Summit's research question: "How do rural communities sustain local journalism that supports democracy?"

One example of a community sustaining rural journalism was the first paper Gulban started, the Rainy Lake Gazette in International Falls, where the paper had closed, and he reached out to the local Chamber of Commerce because he had recently bought his first paper in Grand Marais, also in northern Minnesota. "They got a whole bunch of different stakeholders in town, and we all met, and it was really kind of an amazing meeting for me, because I had never seen that kind of enthusiasm, that kind of spirit, to solve a problem," Gulban said. Three weeks later, they had a paper. "People really embraced it," he said. "We quickly got to more subscribers than, you know, the old paper had."

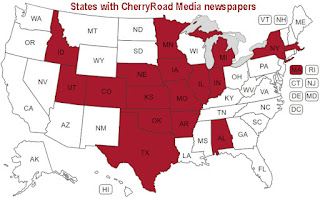

|

| CherryRoad Media map, adapted by The Rural Blog |

Making the papers substantial and sustainable began with returning control to local people. "When we took over, the editors would say, ‘We send in a few articles, and we don't see the paper until it winds up coming to the office after it's printed.’ . . . I think the biggest thing that that happened is they eliminated all the local publishers, so there is no one ... you can call to talk about the paper. There's literally no one. Everything flows up in these vertical silos, which leads to a lack of integration, a lack of working together. And, as you all know, you can't have your salespeople off doing one thing and editorial people doing another. There's got to be that collaboration which, you know, really doesn't exist. . . . If people want to place an ad. They'll call an 800 number, and they'll go online and do it. And we all know in small towns that won't happen."

The downward spiral of news, ads and circulation has left ghost papers with two kinds of subscribers and regular single-copy buyers, Gulban said: "People who just like the ritual of getting the paper and really don't care what's in it ... and people who hold a position in town where they feel like they need to get the paper. . . . People who were truly looking for news had just given up and kind of moved on."

That caused most retail advertising to vanish, and "dependence on legal [ads] and obituaries," Gulban said. "When we looked at at these financials, the revenue from obits, legal and classified, was nearly double the display advertising in a lot of cases, you know, which is totally upside down. . . . So really, what you have is you got a ghost newspaper, right? It really has no relevance in the community. And you know that's a vicious cycle, right? The the less relevant it is. So. This is kind of the cycle that we found most of these papers to be in."

In addition to returning editorial control, "We tried to take out all of the regional or national content that was being put in there primarily as filler," Gulban said. "We still have some national content in some of the more-than-once-a-week frequencies. But anything weekly really has nothing but local content in it. We invested more in editorial positions. . . . We've actually been able to find someone in every one of those markets which has not been easy."

|

| Jeremy Gulban |

But local has its limits. Local ad and page designers are "a luxury that we can't afford," Gulban said. "And we've built our own circulation platform. That's entirely web-based so that we can have people in different locations serve circulation needs across markets." All printing is outsourced, but he said the company might build a plant because so many are closing: "We do believe that a printed product has to be part of the long-term solution" to the problems of local papers.

One way to define a ghost newspaper is that it has no local office open to the public, or is open only a few hours a week: "That just leads to no community goodwill efforts, no sponsoring events, no joining the Rotary Club, none of that," Gulban said. "That's so essential in a small-town newspaper." But not so essential that he has offices in some small markets. In Stephenville, Texas, rent was too high, so "We're trying to pioneer like a shared office, you know, with a Chamber of Commerce, maybe even a local restaurant, you know, we're open for lunch. Three days a week we go in there, the editor's there, the circulation person's there, you can go meet with them. We're trying to be as creative as possible just to keep that physical real estate cost down." The Google listing for the Stephenville Empire-Tribune says it's "temporarily closed."

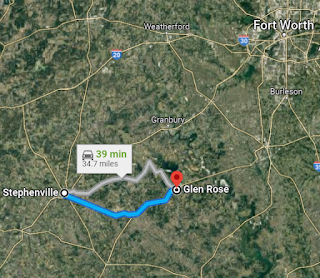

|

| Sites of two of the Texas papers discussed (Google map) |

Gulban's other example was the Hamburg Reporter, in Iowa's southeast corner. Fremont County "had a catastrophic flood in 2019 and basically half the town's population left, so the population is now 890. We have 132 print subscribers and two digital, but we just put the paywall up two weeks ago," Gulban said. But its ad revenue averages $9,200 a month, and "this is the best revenue per population of anything in our whole organization." The paper's mothership is the Nebraska City News-Press, across the Missouri River; the one person "who was basically doing everything" died last month, "so we have to figure out how to handle that. But the model here still holds. . . . We have one person who is about town, knows everybody, is able to do a lot of different things," Gulban said. Our vision, which is a little bit out there, is: If you want to advertise in Hamburg, Iowa, we're the place you should be doing it through, not through Facebook, not through any other technical solution. Because we know Hamburg, Iowa. . . . We want to leverage our local staffs and their credibility to drive revenue in this new digital world."

And America's newest newspaper-chain owner had one broad thing to say about consolidation of newspaper ownership: "I believe strongly in distributed ownership of the news, because I don't think the country is founded on the idea that three or four groups or people would control all the information. The vision was thousands of individual people controlling the flow of information."

Gulban was the concluding speaker at the Summit's morning session. The video is here.

This story has been edited to give the correct genesis of Gulban's paper in International Falls.

No comments:

Post a Comment